I have made it my personal mission to launch a Fleet of 100 Lifeboats in response to the multiple global crises we now face. Recently, a friend asked where this idea came from.

As I was talking through a possible response with one of my collaborators, we realized it’s a challenging story to tell because it involves loops in space-time — the current idea is the result of a previous one that evolved from the one before that, etc. — so how many versions do you need to go back to get the full backstory? Somehow, no matter where you start it feels like you’re already jumping into the middle of the story.

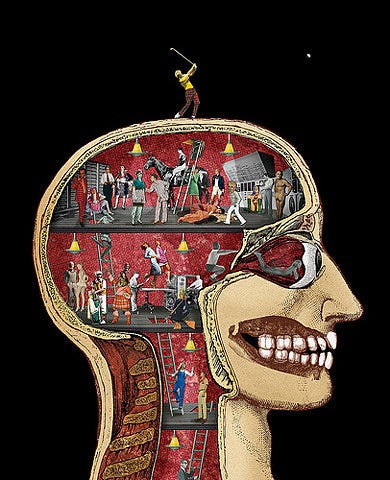

So maybe we should start at the end and work backwards. Ultimately, through all these different iterations, we’ve become convinced that the multiple crises we face are the result of applying mechanistic / analytical thinking to a relational world. The problems are very deep, indeed, in the form of foundational beliefs.

How do you describe water to fish?

We noticed that despite the work of so many well-intentioned, motivated, and energized people, our social and environmental ecologies were and are falling apart; all the indicators are moving in the wrong direction. So, we started to ask ourselves why is that? What’s really going on here? Soon, it became clear, as Einstein said, “you can’t solve a problem on the same level that it was created.” We keep looking for superficial solutions to systemic problems, attempting to use the logic of the current system to heal the problems that very system has created.

So the real solutions require moving people from mechanistic/disconnected to integrated/relational ways of thinking and acting. But how do you invite people into a process that can’t be explained until after you’ve engaged it long enough to develop a new language to explain what you just experienced?

How do you tell the story of a solution that is simple yet complex, that has developed organically, iteratively, collaboratively, from the ground up, synthesizing and juxtaposing interdependent and often dynamically tensioned elements to an audience brought up on mechanistic, reductionist and radically individualistic thinking?

I haven’t the faintest idea. Not coherently. Not concisely.

But not knowing how to do something never stopped me from trying before.

Actually, I suppose that’s the main point. None of us know what we are doing! We face a challenge like none we’ve faced before — a challenge created by our taken-for-granted habits of thought and action. Therefore, relying on our taken-for-granted assumptions and reactions will likely make things worse, rather than better. That’s what’s been happening so far. Lots of folks with the best of intentions have been making things worse rather than better because our reductionist and disconnected ways of thinking keep leading us to make the same mistakes over and over then ignore the obvious consequences of our actions.

The situation forces us to face a basic epistemological question: How do we know if what we think we know is actually true? How do we know what’s really real?

My favourite answer comes from the American Pragmatists: something is true if it works. Of course, that leads us to ask “what does it mean for something to work?” William James uses the metaphor of an archer honing their skill as a model. The goal is straight forward — hit the center of the target with an arrow. The archer “knows” archery to the degree that they can hit the target reliably.

The Reflex Arc

James describes the learning process as a “reflex arc” — a process through which:

- we select the target,

- imagine the actions necessary to achieve success,

- take those actions in the real world, then

- reflect on the difference between expectations and experiences, and

- refine the actions we see as necessary to achieve success.

In this way, we learn and improve subsequent actions; things work better.

The archer moves from absolute beginner who is happy to simply hit the target through to a skilled archer who can begin to account for additional factors such as wind direction or variations in equipment to improve their accuracy by constantly using recent real-world feedback to refine mental models.

While it’s a useful metaphor, most actions in the world don’t have as clear a goal as archery, so we have to go further and apply the model to itself. This was Dewey’s contribution. We make “learning” the skill we aim to develop. We use the system to develop better tools for defining goals, imagining complicated actions and measuring results to allow us to refine our efforts around complex goals. In other words, we learn how to learn. This leads to a sort of meta-process at the core of the Lifeboat Project, an idea taken from Sociocracy 3.0 (S3.0) — treat all decisions as a series of experiments designed to maximize learning.

The basics of treating actions as experiments are simple. We short-hand it as “aim-act-reflect-repeat.” It’s an endless, self-motivating feedback loop in which each step in the cycle references the one before it and suggests the next. So, for example, as we take aim (again), we reference the lessons learned in reflecting on previous actions to clarify the aim itself, which suggests new actions necessary to achieve that aim, which inspires a natural curiosity to take those actions to see what happens.

This is actually easier to do in practice than it is to describe in theory. The reflection process is simply a matter of comparing what we expected would happen with what actually happened in order to refine our expectations and actions moving forward. In other words, the major learning comes from responding to what doesn’t work more than what does (though there’s still valuable information in what works consistently). It’s the gap between expectations and experiences that presents the best areas for learning. In S3.0, we define the gap between expectation and experience — between how things are and how they could / should be — as a “tension.” The gap that causes the tension draws our attention to the richest potential learning.

In the case of the Lifeboat Project, the core persistent tension is the gap between known, validated, patently obvious information about the urgency, severity, and risk of the climate crisis and the complete and utter lack of meaningful action on the part of the social institutions that are purportedly responsible for ensuring our well-being — government, “the market,” media, etc. Our expectation is that these social institutions are there for our protection, but the empirical reality is that the decision-making class are doing everything in their power to prevent solutions from happening while simultaneously working actively to make things worse (for us).

How do we shift our expectations, then, to come closer to match our experience and what are the implications when we do?

Social Transformation

All societies are, in effect, a sort of mass delusion. Society is a set of stories about “how the world works” that often allow amazing things to happen. But sometimes these delusions just don’t work — or rather, they work really well at some things, but cause more problems than they solve overall. They get weighed down by a debt of bad decisions. Healthy societies are malleable and adaptive. They contain feedback loops that allow their stories to transform as their environment shifts. They know the map is not the territory, recognize the negative consequences of choices and adapt accordingly.

Unfortunately, it seems that most (probably all) societies reach a point where they lose their adaptability. They become old, brittle, and fragile. When that happens, the society must re-invent itself to survive, but before that can happen, it must first fall apart.

Of course, societies ultimately exist inside the head — the belief system — of the members of that society. So when societies transform, it only occurs through a fractal process of individual transformation, which feels very much like an existential crisis — because that’s exactly what it is.

So, that’s where the “Lifeboat” idea comes from: a recognition that we need transformation at the person/place/community level. Transforming the world and our communities from an extractive, top-down, capitalist framework to one that is relational, reciprocal and materially-focused starts with our individual transformations, actions and relationship-building in the face of climate crisis and social breakdown. It starts with the individual choice to do things differently, and the more of us there are who make those choices together, the greater impact we have.

How do we re-focus our efforts to care for our spirits by growing deep happiness and resilient mental health; our place — the physical/material health of our local environment; and our hearts through meaningful relationships? We realized that none of these things were possible by trying to do it alone, therefore the health of our relationships and the community are crucial. The Lifeboat Project is all about finding ways to make it easier for people to reach out and connect with the people who are already in their world, to start talking about what’s really real. What really matters, when it comes right down to it?

Because we are coming right down to it.